Welcome to my annual book review. See prior versions here: 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2016, 2015, and all time.

I recently listened to an interview with Kevin Kelly, who has published a half dozen books. He said he’s no longer writing new books, because he believes the center of our culture has shifted to YouTube.

That thought struck a chord. From a young age, I have considered books sacred. I admire people who read a lot: Charlie Munger, Patrick Collison, Ryan Holiday.

For me, the purpose of reading books is to learn and to be exposed to new ideas. I find enjoyment in reading, yes, but that enjoyment stems from a belief that I am learning and growing, in line with one of my core values. For me, reading books is primarily a telic activity.

This leads to two thoughts about reading books.

First, how you read books matters. If the purpose is learning, reading a book from start to finish is not terribly effective. You need to actively engage with the material to learn. That’s why I highlight while I’m reading, save highlights to Readwise, and use the Readwise app to present 10 daily highlights to me, selected from all the books I’ve read following the principle of spaced repitition.

Second, books are not always the best medium for learning or exposure to new ideas. YouTube, Reddit, and ChatGPT may be better alternatives to solve a specific and immediate problem. Academic papers may be more suitable to learn about the leading edge of a field. Twitter, blogs, and newsletters have a higher “idea per word” ratio.

This leads to a few experiments I want to run in 2024:

- Read books more actively. Before starting a book, write down what I hope to learn and what I already know about the subject. Join a book club, and explore if group discussion leads to more insight and better retention. For each (good) book, digest all highlights a few weeks later.

- Consider alternatives to books. Allocate more time to Reddit, ChatGPT, and YouTube. Read papers. Read Twitter. When engaging in alternatives to reading books, maximize learning, by taking notes and adding highlights to Readwise.

I would be very curious to hear what you think of this. Please let me know!

On to my favorite books of the year. I read 25 books this year. See my top 6 below. For the full list, check out my Goodreads.

Tuesdays with Morrie

This book is about a professor, Morrie, who is told he has only a few more months to live. One of Morrie’s former students, the book’s author, visits him weekly for several months to write down his life lessons. The book is on my list because it reminded me how to live well. On this topic, I would also highly recommend David Brooks’ recent essay in the New York Times, The Essential Skills for Being Human. Thank you to Nicolien and Robert-Jan for the suggestion.

How to Live

Some of my friends love listening to audio books. I don’t—I prefer reading. This book by Derek Sivers is an exception. He recorded the audio version of this book himself and it’s a wonderful performance. Like “Tuesdays with Morrie”, this book is about what it means to live a good life. But it is more provocative. In each of the 30 chapters, Sivers evangelizes a certain life philosophy. I found myself agreeing with many different and conflicting ones—forcing me to reflect on priorities and accepting that different moments in life may ask for different philosophies. Hat tip to Han!

Men and Rubber

This book is an autobiography by the founder of Firestone tires, Harvey Firestone. Despite being written in the early 1900s, it’s still very readable. More importantly, as an entrepreneur, I could relate to a lot of the challenges that Firestone faced. The book recounts some fascinating history about the early automobile and tire industry, such as the deal that Firestone struck with Henry Ford to be the preferred tire supplier for the Model T. Thanks Sam for suggesting this gem.

Make Something Wonderful

I don’t consider myself a Steve Jobs fanboy. What I loved about this book, though, is its composition. Unlike other biographies, this book is made up of speeches, interviews, and email exchanges. I found the email exchanges to be especially revealing. One such exchange shows how Jobs made a 180-degree turn after his mentor Andy Grove asked him to speak to an employee. The vividness of the email exchanges reminded me of another business biography I really liked: “The Founders”, by Jimmy Soni, about the early days of Paypal (one of last year’s top reads).

Material World

In 2023, I read a few books about our material world. This was the most vivid. In it, British journalist Ed Conway weaves a fascinating journey through the materials needed for the energy transition—sand, salt, iron, oil, copper, and lithium. The book is chock-full of interesting anecdotes. It also leaves you with a clearer sense of the materials needed to transition to a low-carbon economy. It was similar to Vaclav Smil’s “How the World Works”, although Smil’s book has a broader scope (not just materials) and was a drier read.

The Player of Games

This is a book from the Culture sci-fi series. The story is set in a multi-planetary society (the Culture) in which material wealth is abundant and humans don’t need to work to satisfy material needs. It implicitly poses the question to the reader: what, then, should you do with your time?

The protagonist of the book, Jernau Gurgeh, answers this question by learning and playing games. But just as he gets bored with all the games he has already mastered, he is invited for a grand, highly complex game that will take him years to learn and puts him in contact with another society, the Azad, that doesn’t adhere to the principles of the culture. In doing so, he needs to fully embrace principles that oppose those of his own culture.

Screenshot from

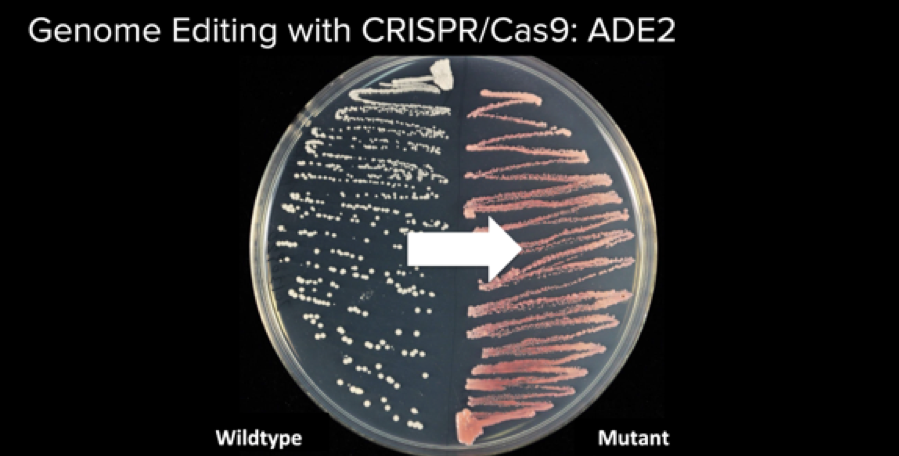

Screenshot from  Our goal was to turn yeast from its natural white color (left) to red (right). Photo courtesy of Will Shindel, Genspace’s instructor.

Our goal was to turn yeast from its natural white color (left) to red (right). Photo courtesy of Will Shindel, Genspace’s instructor.  Screenshot of CRISPRdirect, a website that helps you to identify the guide RNA sequence with the highest likelihood of cutting your gene successfully.

Screenshot of CRISPRdirect, a website that helps you to identify the guide RNA sequence with the highest likelihood of cutting your gene successfully.  The blue, double strand is the original DNA; the purple, single strand of DNA is the inserted genetic material. This screenshot shows how the purple, new DNA is being connected with the outermost 4 base pairs onto the blue, original DNA.

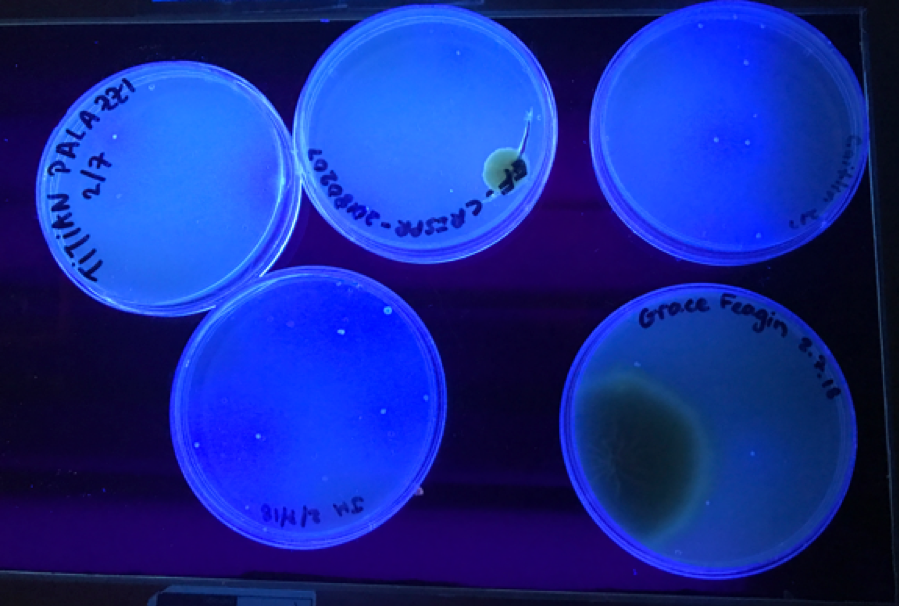

The blue, double strand is the original DNA; the purple, single strand of DNA is the inserted genetic material. This screenshot shows how the purple, new DNA is being connected with the outermost 4 base pairs onto the blue, original DNA. Petri dishes with yeast colonies under UV light. The petri dish top-center and bottom-right show mold growth (this is contamination).

Petri dishes with yeast colonies under UV light. The petri dish top-center and bottom-right show mold growth (this is contamination).